The discussion regarding many of the films up for the Best Picture Award at this year’s Oscars has concerned truth. Mostly this has arisen because so many of the films depict historical events – even if in the case of Zero Dark Thirty that history is quite recent.

Now obviously historical accuracy and film have long been bedfellows so strange that it seems quite remarkable that the issue pops up. It’s not a new phenomenon. Some of the the most beloved and greatest films of all time have factual blips or fudges. The plot of Casablanca absurdly hinges on the possession of letters of transit which have been signed by General Charles DeGaulle. Why on earth anyone in Vichy France – let alone the Gestapo – would value letters from the leader of Free France defies logic to such an extent that the entire film should be laughable. And yet it isn’t – mostly because it is not attempting to depict “truth”. It is about “movie truth”. In movie truth ex-lovers do run into each other in a gin joint and the bar owner is as suave as Humphrey Bogart and the woman is as perfect as Ingrid Bergmann.

Similarly The Great Escape does not depict the actual POW breakout as though it were a documentary – the Americans for one, had been segregated from the British prior to the break out. But again, while it’s clear the movie is tampering with the truth it is being done to depict the historical fact that 76 POWs in WWII broke out from Stalag Luft III and 50 were murdered. The film while taking liberties with time and persons does not break from the core reality of the historical truth. Those events did happen, they may have been harder in real life, they may have involved less humour and action, but if you come away from the film thinking that 76 POW’s escaped and 50 were murdered, then your knowledge of the historical reality is not wrong.

But the character on which Steve McQueen is based did not try and jump the Swiss border on a motorcycle. Does that matter? Not for mine it doesn’t, because it is not the core of the film, nor does it affect one’s understanding of that core truth.

For Kathryn Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty the issue is primarily one of torture, but it is two fold: did torture assist the capture of Osama bin Laden, and does the film suggest that is the case? All evidence suggests that “enhanced interrogation techniques” contributed little if anything to OBL’s capture, and yet the first 40 minutes or so of the film depict torture being used.

Torture is the foundation of the film. The best link we get shown between that torture and the death of Osama bin Laden is a man providing a name long after he has been tortured and which he gives because he has no desire to “go back into the box”. In reality, even this is disputed, and yet Bigelow’s film says it happened. This leads to the overall question of whether this is a film that glorifies or justifies torture at the expense of truth?

Objectively the film does not suggest torture directly led to the capture of Bin Laden, but objectively as well the film spends it first 40 minutes showing you scene after scene of torture and never suggests it is futile. Indeed later on in the film, at a point in time after Obama has been elected, a CIA official bemoans the ability to “prove” that bin Laden is in Abbottabad: “You know we lost the ability to prove that when we lost the detainee program – who the hell am I supposed to ask: some guy in GITMO who is all lawyered up?”

The suggestion that those in GITMO are now all lawyered up is laughable but because no one in the room suggests the character’s statement is invalid, it leads easily to the belief that torture is necessary and was necessary. It also idiotically suggests that those in GITMO are now treated like any other inmate in a US prison.

And so on the other side we have Bigelow and those involved with the film saying they are just showing what happened and taking no sides. Well that is fine if she was also showing both sides, but she doesn’t. I don’t think her film is pro-torture, but it sure as heck isn’t against it either. And that brings us to the movie truth of the film. For people watching the film the clear implication is the first 40 minutes leads to the last 40 minutes of SEAL Team 6 killing Bin Laden. It is not a case of the public misreading the film like those Republicans in the 1980s who thought Springsteen’s “Born in the USA” was glorifying America, rather it is the logical view. You can’t build a film on torture, imply it led to a snippet of info and then suggest “oh we’re not trying to say anything about whether or not it was successful”.

But given this, can we get passed the torture and praise the film in spite of it?

Well yes – and the film is in many respects quite brilliant. The acting is top notch; the direction – especially in the final act involving the attack on Bin Laden’s compound – is excellent. Bigelow is a great director of action scenes.

But I cannot walk past the reality that this film wants to suggest that it is an accurate portrayal of events and yet it also wants to pretend that it is an objective portrayal of those events. The telling of history, just as with daily journalism, is subjective. Choices are made about what to show, what to leave out, what to highlight, what to wash over. I don’t mind films with a subjective view of history, nor do I particularly mind subjective journalism; I despise them pretending to be objective.

I think the film is perhaps one of the best renderings of modern America, by revealing the belief of many in that country that so long as it is being done by America, then whatever being done is right.

The only problem is I don’t think that was the intention of the filmmakers.

Hollywood films not surprisingly have regularly elevated America’s role in historical events. To an extent – so long as the kernel of history is not destroyed – I can cope with that. The Great Escape surely does elevate the role of the Americans, but neither does it suggest it was a US show. Similarly I don’t mind that Stephen Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan would have you think the yanks were the only ones involved in D Day. With that film the great falsehood is that it violates the inner truth that itself had constructed – namely that war is shitty and bloody and random and in which you die and not someone else occurs for reasons beyond logic. The end of that film however shows us that Tom Hanks dies because he set free a German who then returns and kills him. Oh the pathos!!

Argo does not so much elevate the role of the US in rescuing the hostages in Iran as it devaluates some of the role of the Canadians. And yet to my mind this devaluation is slight. It is clear that the Canadian ambassador and his wife were seriously putting themselves on the line and were clearly central to keeping the hostages alive. In the film Ben Affleck’s CIA character talks to the Canadian ambassador as an equal – never suggesting that the CIA was doing all the work; nor suggesting it was a minor thing that the Canadian was doing.

Historical truth in film is often battered like this, the crucial aspect is always whether or not this distorts our view of what actually happened? Last year the baseball film Moneyball depicted the performance of the Oakland Athletics in 2002. The crux of the film was that the team was made up of cast offs and nobodies who were seriously undervalued by everyone. The only pitcher mentioned in the film was a reliever who was referred to as the most undervalued player in the league. Amazingly with this bunch of players, defying the odds and proving that there are different ways to evaluate skill, the A’s get to the playoffs.

After watching the film you would never have heard of Miguel Tejada or Barry Zito. Tejada won the American League MVP that year, and Zito won the Cy Young Award for best pitcher in the league – both had been with the A’s the year before, and were there as a result of some magic new moneyball formula of recruiting. It’d be like making a film about Geelong’s 2009 season and forgetting to mention Gary Ablett Jr.

Moneyball, which is wonderful viewing, suffers the more you learn about the reality. This is always a good guide for judging truth in historical films. In The King’s Speech a couple years ago, Winston Churchill was oddly depicted as being in favour of the abdication of King Edward VIII when in reality (and to be honest, infamously) he was greatly opposed to it. But that does not destroy the crux of the film because it is a mere side note, that would be largely pointless to the narrative even were it not false.

In that same year The Social Network took many liberties with reality. Most crucial was the suggestion that Mark Zuckerberg after creating Facebook and becoming mega-rich was still just a lonely soul wanting to connect with that one woman who dumped him in college. It was bullshit and it’s not surprising that it was written by Aaron Sorkin who also wrote Moneyball.

With Argo it is pretty clear even without knowledge of events that much of what occurs – especially the ending is pretty much “film truth” not real truth. Things occur far too simultaneously – a scene where the CIA quickly approve flight tickets happens in a manner that suggests a damn quick internet connection in 1980. The group are shown to be in danger when they go into a bazar, in reality they never went in to one at all.

Many of the exaggerations are obvious, and I think even Affleck is aware that they devalue the film because over the end credits we are shown the actual photos of the participants next to the actors in an attempt to reinforce the notion that the film sticks close to the facts, or is at least a close representation of it. That alone does I think show Affleck trying to walk both sides of the street – that if documentary and “Hollywoodised” film. Overall however I found the distortions in the film less important than those in Zero Dark Thirty, mostly because my sense was the film was attempting to show film truth rather than real truth. It was a spy film based on events, rather than a depiction of real events and on that score I certainly found Argo the more thrilling picture.

Stephen Spielberg knows all about film truth. When he made Schindler’s List his desire to make the film seem more truthful led him to shoot in black and white because that was the film of documentaries back when the events were depicted. Roman Polanski a decade later when he made The Pianist put paid to that lie that you can only show the truth of the holocaust in black and white film. When Spielberg made Saving Private Ryan he reduced the colour saturation by 60% to attempt to replicate the over-exposed photos taken on D Day by Robert Capa – ignoring that they were overexposed by mistake and thus were not a “real” depiction of the sight on Omaha Beach. For Spielberg reality is that seen in film (or photos).

Spielberg also cannot but fail to stop himself from adding to the events he is depicting with clear hokum. He does this in Schindler’s List with the opening Jewish prayer scene and the ending scene at Schindler’s grave. In SPR he used the character we eventually learn is an Old Ryan to bookend the film and to totally ensure we understand that this film was important and about something. While in Schindler’s List this was more manipulative than anything, in SPR it destroyed the film because it makes the narrative a lie.

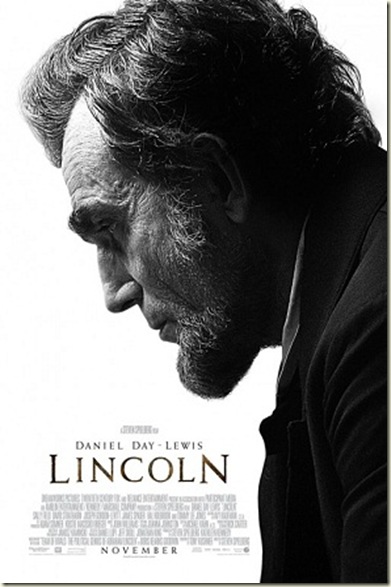

And so when I came to watch Lincoln, I was knew that Spielberg would not be able to contain himself. And from the first scene we see he couldn’t.

The film opens with Lincoln sitting while watching troops walk past in the rain at some army camp. He is confronted by 2 black soldiers. Normally this would be a quick “good luck men” type scene, but luckily, Spielberg has found himself the most articulate and forward thinking black soldier in the Union Army. Rather than any deference to his Commander in Chief, this soldier delivers a proto-Malcolm X type speech and then soon after helps out two white soldiers by completing a recitation of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

Well now.

In elementary schools throughout America today there most likely are people who know the full text of that speech, but it fairly well beggars belief that any soldiers while fighting in the civil war would have had the time or inclination to memorise the speech, let alone the awareness of the speech’s existence.

From that opening scene I was on guard and to be honest I viewed the entire film through the shadow of Spielberg’s need to stick to movie truth. When I heard about the fact of Congressmen from Connecticut voting for the abolition of slavery despite the film showing them voting against, I was neither surprised, nor bothered. The film is not about those congressmen, nor does the fact that the historical flub was done to heighten the tension of the final vote ruin the crucial truth of the film. What mattered more to me was that I felt very little tension at all during that scene of the final vote.

Seeing Congressmen who have only briefly been shown the previous 2 hours getting up and saying “Yay” or “Nay” rather lacks tension when you don’t even know if those Congressmen were expected to vote one way or the other. The film suffers from a case of the “we know what happeneds”. We know the vote passes because we know Lincoln freed the slaves. That’s why making your film’s climax an event we all know happens is very tricky. It’s why it is best avoided. It’s why William Goldman chose to end All the President’s Men with Woodward and Bernstein stuffing up and showing the Nixon resignation only on the teletype ending.

Lincoln is about the passing of a vote we all know will pass. We do discover some interesting things along the way, but it never deviates from that path. Ironically for a film adapted from a book called “Team of Rivals” we get very little on the rivalry. Tommy Lee Jones’s character Thaddeus Stevens is shown to be opposed to Lincoln’s more moderate path but the two characters largely exist separately in the film. There is more rivalry between Stevens and Lincoln’s wife, Mary Todd, than with Lincoln, and indeed there is more rivalry between Lincoln and Todd than there is with anyone else.

The Abraham Lincoln in the film is a folksy saint. That might be the truth but I knew going in that if there was to be any other side to his character, Spielberg sure as heck is not the director who would show it. Whether or not the film deviates from historical truth or not was of little concern to me, the bigger concern was that really, I didn’t care. When Lincoln is assassinated I felt little loss. It was just the end of a history lesson. I was more moved when watching the events being related in Ken Burns’ documentary, The Civil War. That’s a major fault in any film, let alone one where the person dying is the name of the film.

Quentin Tarantino is not one for worries about historical accuracy. His Django Unchained plays loose with the facts from the get go when the opening credits state it’s 1858 “two years before the Civil War”, which is odd given the war began in 1861.

I know – who would’ve thunk it.

Tarantino is a post-modern film maker. He has his characters use modern slang, wear sunglasses and use weapons at a time clearly before they were invented. He and his many, many devotees will dismiss any criticisms by suggesting he is standing on the shoulders of giants and rendering something new – twisting it though a new paradigm perhaps.

Yeah, but so what?

He has stated his desire with this film was to make a western for black kids to be able to watch and see a black man as the hero. And I guess if that is what you want to do then you might as well do it if you have the money and power as does Tarantino. Except he hasn’t made a western, he made a film set within the genre of western films. His film is to westerns as Sleepless in Seattle is to rom-coms, which wasn’t really a rom-com but a rom-com about the romance and comedy in rom-coms. The best westerns are not about depicting a great western movie, they are about depicting life – think The Searchers, Once Upon a Time in West, Red River, Shane even Rio Bravo.

Those films – especially Once Upon a Time in West, did often draw in the history of film, but they were about more than just showing they can do that. They have a core to them that is completely lacking from Django Unchained. Mostly because great westerns – like great films – contain fully developed characters; Django Unchained, like all Tarantino films – contains flatly developed caricatures who have great lines to say, but very little to think.

Whether or not the events depicted are true representations of history is irrelevant because the characters involved in those events are not true.

Who cares whether Mandingo fighting really occurred or not, what is of greater concern is that the Leonardo DiCaprio character who watches the fighting is not a real person. He doesn’t talk like a real person – he just delivers Tarantino lines. There’s no inner workings going on; he’s just a dialogue spouting machine. So too is the main character, Django. The device of Django seeing his wife in hallucinations is no substitute for actually writing scenes that explain to the viewer why there is such love. And when we finally meet his wife, she might as well still be a hallucination for all the part she plays in events.

The film has a great first hour, Django and Christoph Waltz’s character, Schultz, are a great team. I was happily going with them on their travels – the scenes involving the shooting of the sheriff and the Ku Klux Klan attack are great fun. But when they turn towards Mississippi and go rescuing Django’s wife, the film quickly becomes boring – tedium interrupted by scenes of violence that only further dull the senses or slap you about with a “look at this I’m showing how shocking things were… or weren’t who knows, Django is wearing sunglasses and talking like someone from Harlem 1970 so it all might just be a post modern bit of reworking of history”. That’s the problem with being so overly post-modern. You can’t toy with history and time and then demand to be believed when you perhaps are trying to depict something as literal truth.

Many people have questioned the use of “nigger” in the dialogue as though they would think some other word was used at the time. I had no difficulty with that word, however, whenever the slave “Stephen”, played by Samuel L Jackson, uttered the clearly post WWII phrase “motherfucker”, I was reminded again that this was a Tarantino film and truth was secondary to snappy dialogue and violence.

By the time the film enters the last 30 minutes, reality is long gone and the arrival of Tarantino himself sporting an Australian accent only serves to reinforce the stupidity of it all.

Only one scene, involving the Schultz character, shows any depiction of some inner truth. Schultz, a German is remembering seeing a slave being attacked by dogs at the bidding of slave owner, DiCaprio. While he remembers the horrific scene a woman nearby is playing Beethoven on a harp. He demands she stop as though the beauty of Beethoven should be divorced completely from a world where such evil could occur. The scene is excellent not so much for the addition it makes to the narrative but because it reminds the viewer that Schultz’s Germany which spawned Beethoven will also give rise to the evil of the holocaust. Schultz is also by far the best character in the film. The one person who almost approaches someone who might have once actually existed in a place on earth rather than only in Tarantino’s imagination.

The film is not even a very good western, let alone a film deserving of being nominated for Best Picture. It would be great one day to see Tarantino make a film that doesn’t explicitly reference films/genres from the past. It would be good to see if he can write a real character instead of someone who always knows the right thing to say at the right time. That will never happen of course. Not while he is getting rewarded and praised for making films like this.

PART TWO tomorrow.

Of all of the listed films I've only seen Zero Dark Thirty (after realising Django was a Tarantino film I steered clear), and to be honest I just couldn't buy into the protagonist, Maya. There seemed to be a lot of "In case you hadn't noticed I'm a woman in a man's world, so I'm going to be abrasive and swear a lot, and the brass are going to chuckle and give each other the 'spunky chick' look. I'm hard core don't 'cha know?". I'm assuming that was intentional, to set her apart from the rest of characters, to show she's different in continuing the chase.

ReplyDeleteThe assault on the Abbottabad complex was a nice contrast to the usual Hollywood portrayal of Special Forces.

Re: the torture it did seem indulgent, and to go on...past the point of usefulness as a storytelling device imo. Again it seemed to be used as a device to establish that Maya is the real deal, ready to do whatever it takes.

Re: historical truth vs movie truth, from reading a couple of articles about the film it seems Bigelow etc. have tried to have their cake and eat it: claiming historical accuracy, but when pressed falling back in the "It's only a movie." defence, which is weak.

I think you're being too harsh on Tarantino because you're missing an important element of his films: sheer fun.

ReplyDeleteI honestly don't care if a film is unrealistic. And if a film makes little attempt to be realistic, I welcome highly stylised lines that a normal, everyday person wouldn't say.

Tarantino makes films that are pure entertainment. And to my mind, glorious entertainment.

His last two films have been revenge fantasies. They should be judged critically as fantasies.

Tone Master Tone - sure it's fun - though my fun left in the last half of the film. But I want a bit more from the Best Picture nominated films than fun.

ReplyDelete@ToneMasterTone

ReplyDeleteI love Tarantino films, and I love spaghetti westerns. I thought a combination of the two would be amazing. This film could have been good, it could have been great, but it was neither.

Grog did not miss the important 'sheer fun' element of the film, it was there, but after the first hour, it was patchy at best. It was probably the most un-fun Tarantino film I've ever seen - I spent most of the last half of it playing sudoku on my phone.

It needed much tighter editing, complete removal of some scenes and characters (eg the wife should not have been alive for a proper revenge film), and decent explanations of the relationships eg between Candie and Stephen (I mean, WTF?? although maybe I missed something while playing sudoku).

I'm just glad I didn't pay to see it. I also can't believe it won the best screenplay award - further proof that the Academy Awards is complete bollocks.