Today the ABS released the latest labour force numbers. I haven’t done a full post on the number for a couple month due to the election, so let’s have a look and see how we’re doing.

First off, the numbers scream “ignore the seasonally adjusted rate”. On seasonally adjusted terms the unemployment rate in September actually fell from 5.8% to 5.6%.

But come one. Really? Maybe it’s the big turn around, but given the IMF on Wednesday thinks we’re looking at a 6.0% unemployment rate next year (and Treasury is gloomier still, thinking 6.25%) I’d bet no.

In trend terms – which is always much better when it comes to comparing changes from month to month, it stayed flat at 5.7%.

And anyway if we get down tot he nitty gritty, the seasonally adjusted figure in August was 5.7647% so it only just got rounded up to 5.8%, and September’s number was 5.6479%, so it only just got round down to 5.6%. Thus while it looks like a 0.2 percentage point drop it’s really only a 0.12 percentage point drop.

So I’m going with the 5.7% flat rate as more believable.

OK, the 5 year picture:

We’re not quite back to where we were during the GFC, but the path back to 6.0% has been pretty steady since mid 2012.

So let’s go in for our 18 month close up:

A steady rise, but and ever so slight suggestion of a plateau. I think that plateau depends a fair bit on whether or not this month’s figures get revised a bit next time round.

But that’s the big number, let’s flip open the hood and have a bit of a squirrel around and see what is really going on.

First, monthly employment growth:

There was an increase of 9,100 jobs in seasonally adjusted terms, but employment actually fell in trend terms:

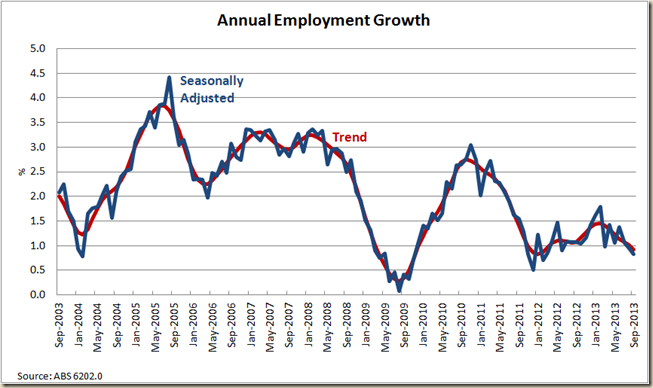

Either way, it’s pretty soft (and by soft I mean fricken weak) as the annual employment growth rate really shows:

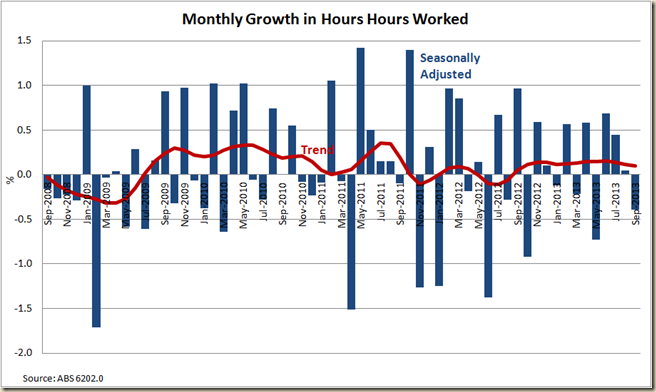

The hours worked measure is also interesting. In seasonally adjusted terms it fell (even though the amount of jobs increased). But in trend terms it has been increasing for the past 12 months:

This translates into an annual increase in hours worked that seems a bit at odds with the employment picture:

But it makes more sense when we look at what has happened with both over the past few years:

Here we see is that in 2012 hours were cut back, but employment continued to grow – through hours of full-time work being reduced, and/or the growth in part time work exceeding full time work. It is not too bad a thing really – much better for hours to fall than for total jobs to – it is always easier to increase hours than to go from no job to a job (and also a sign of a nicely flexible IR system).

Now we see a bit of a counter balance. Clearly the economy is not going gang busters, but where work is able to be increased it is being increased through either shifting part-time workers to full-time, or increasing the hours of full-time workers.

I would suggest the space between the total employment growth line and the hours worked bars from June 2012 to July 2103 exhibits a lot of spare capacity in the labour market of those already employed.

I would suspect that the hours worked growth will need to stay above the employment growth for a few more months before we have any chance of seeing a good increase in employment.

As a result the Hours worked per employed has now risen for the past 6 months, but is still well below pre-GFC levels:

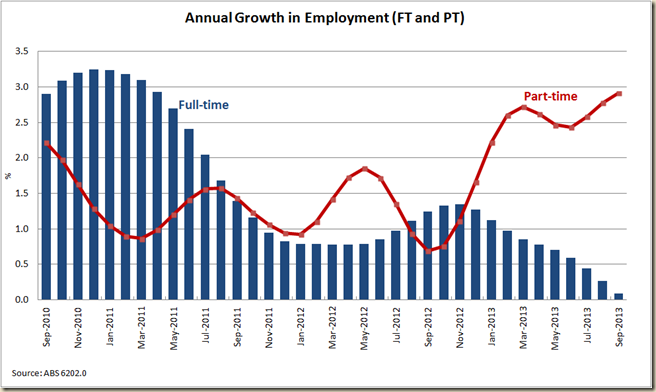

So there is some employment growth but not much, and what there is, is mostly part-time

But even the part-time employment growth is slowing as can be seen pretty starkly when we compare monthly full-time and part-time employment growth:

Not surprisingly the unemployment rate of those looking for full-time work remains well above the total rate:

The gap has narrowed a bit, but looking back over the past 10 years, we see the gap is as big as it has been outside the GFC period:

The Participation Rate has received a fair bit of attention today, and not surprisingly because it has rather dived in the past few months:

Now it is always worth remembering that the participation rate can fall for a couple reasons. The first is the most obvious – people have given up looking for work. But the second is why they have done that. For some it is due to despair, for other it is due to age.

The ageing of the population remains with us, and I seriously doubt we’ll see a participation rate ever again at the near 66.0% that it reached in late 201o.

Indeed a look at the past 20 years suggests 2008-2012 was a abnormal level rather than the expected to be norm.

One thing to note is that since November 2010 the total participation has fallen 0.8 percentage points, but the 15-64year old participation rate has only fallen 0.3 percentage points in that time.

People are getting old, more than people are getting discouraged. For a better look at the ageing dynamic, Matt Cowgill has some excellent graphs on it all. My very quick and dirty look at the impact of the ageing of the population is to compare the change in the total employment to population ratio and that of 15-64yo since April 2008 (the peak level).

While during the GFC the both rates fell and rose around the same, since the end of 2010 the total rate has fallen faster. And as we know 2010 minus 1945 is 65 – or the beginning of the retirement age for baby boomers.

(I really should use the 25-54 age bracket, as what we’re also seeing now is that 15-24yo are staying in school/uni/TAFE more than they sued to, which is also reducing the total rate somewhat).

OK, now onto the growth of employment for men and women. Usually I look at total employment, but let’s just look at full-time work:

For the first time since the GFC period, annual male full-time employment fell in the past 12 months. While full-time employment for women is holding up, growth has moderated in the past 12 months.

Not a really wonderful picture of economic health. Yes the unemployment rate went down, but let’s not get too excited, when full-0time work numbers start picking up, then we can begin to say the corner has been turned.